We get out of the car and immediately a sense of silence comes over us. It is calm here and so quiet that I wonder whether the people who live in these rows of houses had heard the car doors slamming. Perhaps they will become aware of us in the moment they look through their windows and see our car’s foreign number plate. For a second I feel like I have broken into an idyll where I do not belong and immediately catch the residents’ attention. However, what do I realize immediately when standing on the main street of the town: who could notice me? I do not see a single person.

I am here in a small Istrian town called Raša, forty kilometers away from the regional center Pula and six kilometers from the town of Labin. All I know is the fact that this is a place built with one single objective: to dig coal.

On 4 November 1937, the town was opened. It had been built in 547 days during a time when Istria belonged to Italy. Its designer, the well-known architect Gustavo Pulitzer Finali (1887–1967) from Trieste, intended that the town house 6,000 inhabitants. This youngest and in many aspects the most particular town in Istria was supposed to be a fascist model town. It was not only intended to house the miners of the nearby coal mine but to also afford them bearable living conditions. Yet, if you take a look at the literature on Raša, especially from the socialist period, the town is called a “mining ghetto,” a place with a dehumanized atmosphere, a city of depression. But what is the town really? My essay will follow this question by tracking Raša’s miners and their culture.

I look at the street in front of me feeling as if I am standing in front of a film set, in which there are currently no actors. Immediately, at the first house I notice graffiti on its facades. I can decipher “Tražimo Titu” barely recognizable as the colors have faded away. Since we seem to find no people, I ring the first door. I expect a grumpy, old miner who does not want to have a conversation. However, the door is opened by a slightly older, smiling woman. I introduce myself and simply ask her how long she has been living here. She tells me that her daughter from Pula lives here during the summer months with her husband and child, so they can rent out their house during Pula’s tourist season. Furthermore, she says that the house has two entrances and that they live only on the lower floor. She herself does not live here, but visits her daughter. She explains that no family member has any connection with miners or the mine. She does not know the neighbors closely by. The letters on the facade were already there when they bought the house. Thanks to her hospitality, she lets me in and allows me to take a photo of the facade from their garden, where more graffiti is clearly visible. She shows me the entire apartment, which is relatively small and equipped with modern furniture. In the bedroom, my gaze lingers on a dresser that does not match the rest of the interior. The woman explains that this very old wooden chest was already here when they moved in and her daughter retained it, because of its good condition and high quality. The question that arises for me is, who lived here before? Did every miner have such an apartment that was equipped with solid wood furniture?

This is how the historical information on the Tourist Board’s website describes these houses:

“This part of the town was built in the first phase, just after the Krapina Lake was drained. There are 77 one-story workers’ houses built with four comfortable two-bedroom apartments, each with a separate entrance. On the ground floors the doors alternate to avoid the monotony of repetition. Each apartment was separately equipped with about 200 square meters of garden, which was mostly cultivated by women – their own contribution to the landscaping of the city, which places Raša among the so-called garden cities. An interesting fact is that Pulitzer also designed the standard furniture for the workers’ flats, like for example the high-quality chest.”

It is apparent that the city was built for the workers of the surrounding mines. As you walk through the streets, next to the terraced houses you can see other buildings reminiscent of administrative buildings. Examples are buildings with the sign Casa di Tipo E e F. If you dive deeper, you will find out that this is a comfortable three-story building with a total of 22 rooms, which housed unmarried clerks from the mine administration. Likewise, in the upper part of the city, an F1-type house was built behind the church as a two-story house with six mini-apartments for the needs of single engineers. Both complexes were redeveloped into residential buildings after the mine closed in 1966. A comparable type E House was intended for the accommodation of single miners, for miners who had the status of temporary workers and for permanent workers without families in the Raša area.

After the end of World War II, the Istrian coal mines, Raša included, were of great importance for the economic reconstruction and development of Yugoslavia. At that time the maximum number of employees was around 7,000, and the highest level of coal production was reached in 1959 with 860,100 tons. However, in the 1960s cheap oil led to a decline in the use of coal, which led to a decline in its production and in the number of workers employed by the Raša mine. Large inventories of unsold coal lead to the gradual closure of coal mines. Coalmining in Raša was discontinued in 1966; the mines in Labin and Ripenda (near Labin) were closed in 1988, and on 29 November 1999, the last coal mine in Croatia, Tupljak (also near Labin), was closed. While walking through the streets of Raša, we discovered clubs for pensioners and a fire station, each with miners’ symbols, and two children playing with each other. But overall, the town looks very deserted and lonely.

Our next stop is the square with the St. Barbara Church. The architect Pulitzer paid special attention to this town quarter. The church is built in the form of an overturned carriage for the transportation of coal, which also resembles the entrance to the shaft, above which is a bell tower – a symbolic shaft tower that lowers and raises miners to and from the pit. On the other side, as an annex to the church, the space symbolizes the underground mining gallery.

What is striking here is that there are no windows inside the church. Once we had arrived in Raša, we immediately noticed that no road leads directly to the main square, but all roads pass it. Here, one also gains the impression of an almost extinct urban life. However, one is surrounded by symbols that point to a certain time. Their message is easy to understand today: they point to the determination to accomplish one specific aim, that is, to exploit the rich deposits of coal. However, any town life, if there was any, must have taken place here. Clustered on this relatively small square, there is a supermarket, a post and telegraph office, the mine headquarters, and a café where, unusually for Croatia, there was no one inside. I try to imagine what it must have been like back then, when Raša bustled with life. Andrea Matošević writes that

“On photographs from the time immediately after its construction, and even today, Raša is always shown as a blank square, in the absence of humans, as a frame that was the backstage, conceived and realized in a time of industrial progress, for the production boom (and not in the spirit of the producers, the workers).”

All architectural elements point to the intention of fusing the town and the mining culture, which dominates every meter of the newly built site. However, the emphasis is on the function and appearance of the town’s architecture rather than on the inhabitants. Although Raša today is a rather depressing place, we were amazed at how much we could still recognize from the past: the primary school, the kindergarten, the mine directorate, the mine hospital, sports centers, the police station, the mining canteen and also the Raša mine itself – only that most of it is now out of use.

On the way to our car we try to find out where the once popular cinema is located. An elderly man comes to meet us, and we ask him. He walks us to the cinema and tells us that parts of it had burned down. He answers politely, but he speaks to us as if crushed and without looking into our eyes. We ask if he used to work in the Raša mine. Walking by, he says: “I worked here, later I worked in Labin.” From the way he replies to our yes-or-no question, it transpires that he felt a strong identification with the mine; his reply sounded like a proud but also rather ritualized answer, as if he had repeated it very often.

We then drive on to Labin, because we saw the former miner’s words as a new clue. At the exit from Raša we see a poster commemorating the miners’ work.

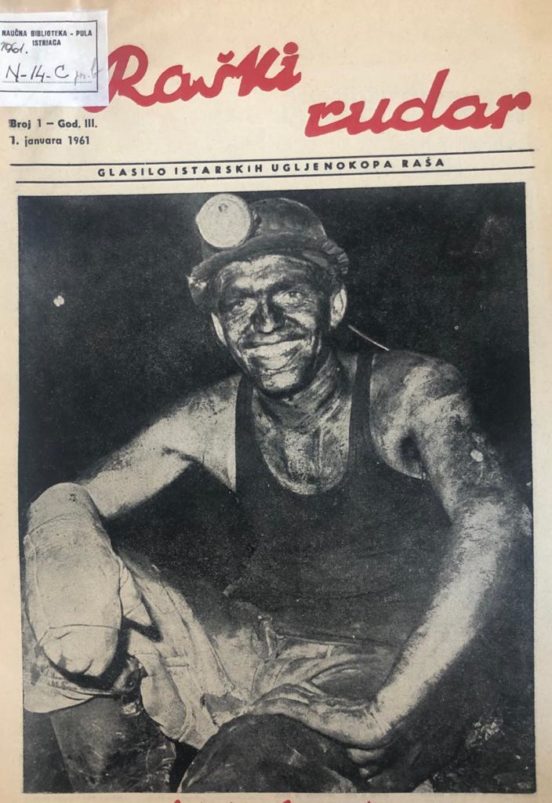

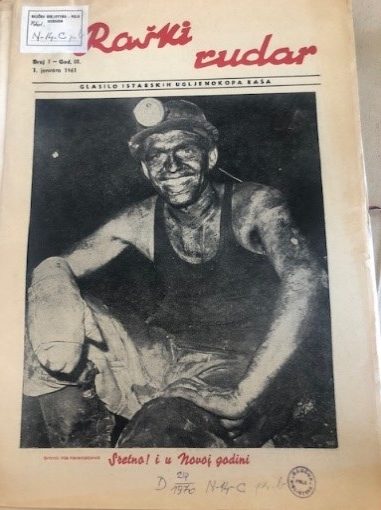

The poster seems familiar, as such pictures were often seen in the newspaper Raški Rudar, which was published twice a month when the mine still operated.

The difference between the pictures is portrayed by the facial expressions of the people. Maybe one of the two pictures shows the truth while the other shows a truth that should be portrayed.

Once in Labin, a mining atmosphere is not obvious at all. Except for a museum, which explicitly deals with the history of mining, a visitor does not feel much of a mining culture. In the old town of Labin we find a regional museum, which is promoted in almost every brochure of the city. In addition to local archeology and folklore, the museum also has a walk-through coal mine reconstruction with appropriate sounds and old equipment. The exhibition shows how it was miners who shaped this region for a long time. The special attraction is the permanent mining exhibit, which reflects almost four hundred years of mining history. It is situated on the ground floor and the basement of the museum building. It was built between 1961 and 1964, with the direct assistance of Istrian coal miners from Raša. By using objects that were once used in the mine and imitating a corridor of about 150 meters in length, an attempt is made to simulate the ambience of the mine as accurately as possible. The display covers all the characteristic features of the mine: railroads, wagons, different types of subgrade, an excavation site, conveyor belt, tools, various devices and equipment.

We are on the way back to our car, now planning to leave this region of miners, amazed at how much past we have felt today. In my head, the motivational signs from entrance to the main square of Raša and pictures of the supposedly lucky miners are buzzing. Pictures that try to hide the gloominess of their everyday life – an everyday life that the tunnel illustrates very well.